Early in 2018, the European Commission proposed the introduction of extended producer responsibility (EPR) for fishing gear and Defra signalled their intention to explore the merits of such a system in their 2018 Resources and Waste Strategy.

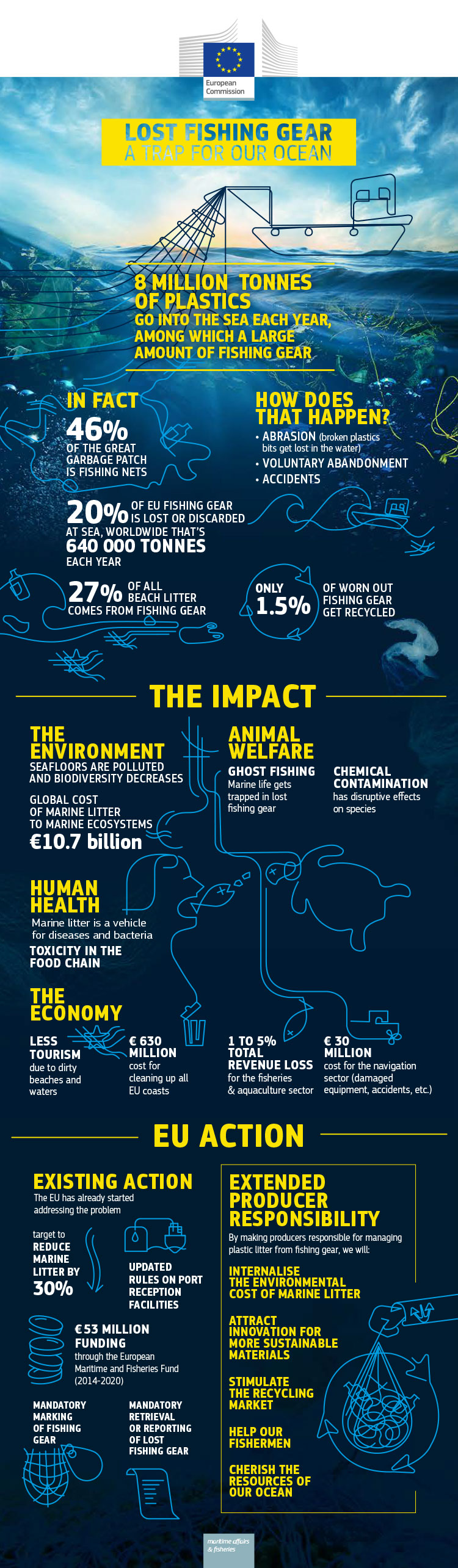

For the average citizen, how the fishing industry is regulated may seems somewhat esoteric. While this may be true, the reality is that designing an impactful EPR regulation for fishing could have a much greater impact on marine plastic pollution than some of the headline grabbing legislation the government is currently considering, like bottle deposits or a plastic packaging tax (see the European Commission infographic at the end of this article for the sobering facts about marine pollution).

Low/no recycling

According to the EU Commission, just 1.5% of fishing gear is recycled. Plastics are used to ensure durability, but the consequence is that these items take many hundreds of years to degrade.

Consequently, fishing equipment is estimated to account for 46% of the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Design houses, such as Burberry, have started to produce yarn that proves the concept of recyclability, but they are still a long way off becoming a significant buyer of “waste” material from fishing.

Ghost fishing

“Ghost fishing”, where nets, lines, pots and traps continue to trap marine life long-after they have finished their intended purpose, has become increasingly common. Images and videos of entangled wildlife go viral on social media and it is clearly a hugely emotive issue for the vast proportion of consumers - when it becomes visible on our timelines.

Meanwhile many people watching Blue Planet II have rushed to replace their coffee cups and plastic bottles with reusable alternatives and many packaging producers have made commitments through the UK Plastics Pact in order to reduce their impact.

However, the stark reality is that fishing could account for twice the volume of plastic pollution as inland-based activities.

What does the EPR regulation need to do?

Specific EPR policy must balance the need to reduce litter with creating a viable market for the secondary materials. These two desired outcomes are not always the best of bedfellows.

For example, to reduce litter, one might look at bans, fines or taxes, rather than EPR. Similarly, the UK government could go some way towards creating a market for recycled materials by expanding their ideas for a Plastic Packaging Tax to included other plastic products, such as fishing nets.

The reality is that policy will need to be designed in such a way as to capture both valuable and non-valuable materials.

Meaningful secondary uses

Many different organisations have demonstrated that fishing nets can be used to create new high-quality yarn to make products as diverse as socks and carpets.

In fact, when Ecosurety moved offices earlier this year we specified a carpet that was made from waste fishing nets. It was just one specification amongst many to reduce the impact of our office fit-out, but the educational value is significant when demonstrating to employees and visitors the potential secondary life of these polluting materials.

The Ecosurety board room

Significant challenges

There are numerous challenges that will need to be surmounted for EPR to make a meaningful impact. Sorting and recycling the mix of materials and colours used for fishing equipment presents a significant challenge, which mirrors the problems of the plethora of plastic packaging polymers and other short-use plastics.

As with any maritime regulation, the logistics of monitoring practices is another challenge that requires significant support from fishermen. Given the difficulties of monitoring land-based regulations, significant resource would be required to ensure that fishing activities are adequately policed. How we manage our seas has been an unresolved debate that has continued for many years and has clearly included many more issues than just fishing equipment.

Costing in the negative impacts of “ghost fishing” and the prevalence of litter will also be complicated as Defra are already finding for packaging waste. Trying to pin irresponsible and illegal behaviour on a producer is difficult. However, incentivising producers to create a product that is simply too valuable for anyone to think of discarding may be a possible solution.

'When' rather than 'if'

The UK Government’s specific commitment was only to have reviewed and consulted on two new regimes by 2022, which could focus on several different potential wastes. There is no guarantee that they will choose fishing nets for new policy in this timeframe.

However, as the Resources and Waste strategy outlined, the Government are “are supportive” of EPR for fishing in the EU and that they “expect to review and consult on our own EPR scheme.”

While there is lots on the agenda at Defra, this sentiment suggests it will be more a question of “when” a new law to reduce the impact of fishing gear will be implemented, rather than “if”. Let’s hope it isn’t the one that got away.

You can read more about other future EPR on our dedicated page, including textiles, construction and tyres. If you have any questions for our team, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Robbie Staniforth

Innovation and Policy Director

Robbie is innovation and policy director at Ecosurety. Having spent years building an intimate understanding of the industry’s policies and politics, he uses this knowledge to help shape new legislation and oversees Ecosurety’s growing portfolio of cross-industry innovation projects including Podback and the Flexible Plastic Fund. He has worked closely with Defra during the most recent packaging consultations, outlining the impacts and required transitional arrangements of the UK’s new EPR system and is a member of the government’s Advisory Committee on Packaging (ACP). He is also a spokesperson for the company and regularly uses his influence to communicate the importance of environmental responsibility to external stakeholders.

Latest News

Q2 2024 recycling data shows strong performance in H1

By Sam Marshall 24 Jul 2024

Ecosurety continue to step up for refill and reuse

By Victoria Baker 24 Jun 2024

Ecosurety renews B Corp™ certification with flying colours

By Louise Shellard 11 Jun 2024

Ecosurety sponsor the 2024 Carbon Literate Organisation Awards

By Louise Shellard 07 Jun 2024